Story of the Lost Gunners Quadrant

In 1895, the aging former commander of the

Confederate Fayetteville Arsenal, Lt. Col. Frederick L. Childs,

passed

away

and was buried in the quiet cemetery of the Church of the Holy

Cross in

Stateburg,

South Carolina.[1]

The old

Confederate veteran went to his grave without ever recovering

a

treasured

piece of his father’s military past that had been passed down to

him.

Childs’s

gunner’s quadrant and other personal belongings fell victim to

Sherman’s engineers when

they

razed the Fayetteville Arsenal. Amazingly, almost a century later,

the

quadrant

was returned to the Childs family under the most curious of

circumstances.

Frederick L. Childs was the only son

of an

American military hero, Bvt. Brig. Gen. Thomas Childs. Thomas

Childs

entered

the United States Army in 1814 at the tender age of 16, while

the

country

was at war with England.

While a

cadet at West Point, Thomas accepted

an

early commission from the Army to help meet the needs of the

service. The

teenager

led his detachment against British forces at the 1814 Battle of

Fort

Erie.

The young lieutenant distinguished himself during the battle by

capturing

British

Artillery Battery No. 3. After killing or capturing the

British

soldiers

manning the battery, Childs and his men spiked the guns and

destroyed

the

powder magazine. The valuable ordnance materiel seized by

young

lieutenant’s

detachment was then turned over to the War Department.

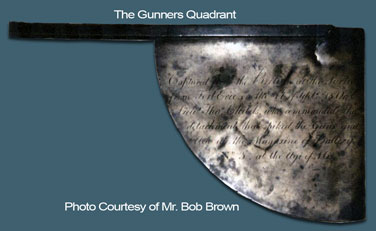

Congress commended the bravery of

Lieutenant

Childs during the battle by having one of the captured

brass

gunner’s

quadrants engraved and presented to the young officer. The

inscription

read as

follows: "Captured

from

the British at the Sortie from Fort Erie

on he

17th of September, 1814, by Lieutenant Thomas Childs, who commanded

the

detachment

that spiked the guns and blew up the magazine of Battery No. 3,

at

the age

of 16."

Childs served in the Army for

another

39 years, rising to the rank of brevet brigadier general. He

died in

1853

while serving in Tampa,

Florida.

Following his death, his

only

son, Frederick L. Childs, became the steward for the treasured

quadrant.

Unlike

his father, Frederick graduated from West Point before joining the

ranks of the United States

Artillery.

Throughout his service in the United

States

Army and the Confederate Army, Frederick Childs carried the

quadrant

with

him. As Sherman approached Fayetteville in March 1865,

Childs

accompanied

the materiel and equipment evacuated from the Arsenal, leaving

the

quadrant

in the care of his mother and sister at their residence on the

Arsenal

grounds.

Following Sherman’s

arrival

at the Arsenal, Mrs. Childs approached the general, seeking

protection

for the

family’s property. She hoped Sherman

would

show leniency to her based on the Union commander’s relationship

with her

late

husband years earlier. Rebuffed by Sherman

for her son’s traitorous acts, Mrs. Childs was left to the mercy of

Sherman’s men, who showed

little

sympathy for the aging widow. Their quarters and all of their

personal

belongings

were either destroyed by fire or dumped into the Cape

Fear

River along with other items from the Arsenal.

From 1865 on, only the story of the

quadrant

was passed down through the Childs family. But this story had a

happy

ending.

In 1932 a night watchman at the Norfolk Naval

Hospital

named Paul

Watson

learned that a patient, Marine Corps Lt. W. W. Childs, had been in

a

traffic

accident and had been admitted for treatment. The curious

Watson gained

permission

to visit Childs from the hospital staff.

Watson introduced himself to the

lieutenant

and informed him that his father, a salvage diver, had dived

the

Cape

Fear River in the early 1900s in an effort to recover scrap metal

from the

Arsenal

dumped there by Sherman’s

men.

His father discovered an engraved brass gunner’s quadrant inscribed

to a

Lt.

Thomas Childs. The elder Watson decided to hold onto it in

the hope of one

day

identifying its rightful owner. The years passed, and the

quadrant was

handed

down to another generation.

After hearing Watson’s story,

Lieutenant

Childs informed him that Lt. Thomas Childs was his

great-grandfather.

Coincidentally, Childs happened to have the military

commissions

of his great grandfather and grandfather in the car with him on

the

day of

the accident. He showed the two commissions to Watson, who

did the noble

thing

and returned the quadrant to its rightful owners, his family’s

mission

finally

completed. One can only imagine the delight felt by

Lieutenant Childs

to have

so treasured and storied a military item back in the

family’s

possession

after so many years.[2]

[1] “Historic Old Southern Home,” Confederate Veteran, vol. 37, April 1919, p. 130.

[2] Mrs. Stephen E. Puckett, “Long Lost Present From Congress To Young Officer in War of 1812 Recovered by His Great Grandson,” Columbia S.C. State, September 4, 1932.

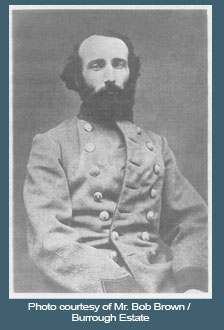

Lt. Col. Fredrick L. Childs